Erich Robinson-Tillenburg

The Magic of Working with a Team to Achieve Your Dreams

I, Charley Morton, time traveler and science geek, have set out to record my interview with a college student and inventor of a new form of hyper-fast transit as part of my "Superheroes of History" project.

The biggest thing is really learning how to learn. Constantly question what everyone else is accepting as the truth because, a lot of times, there will be a better way of doing things.

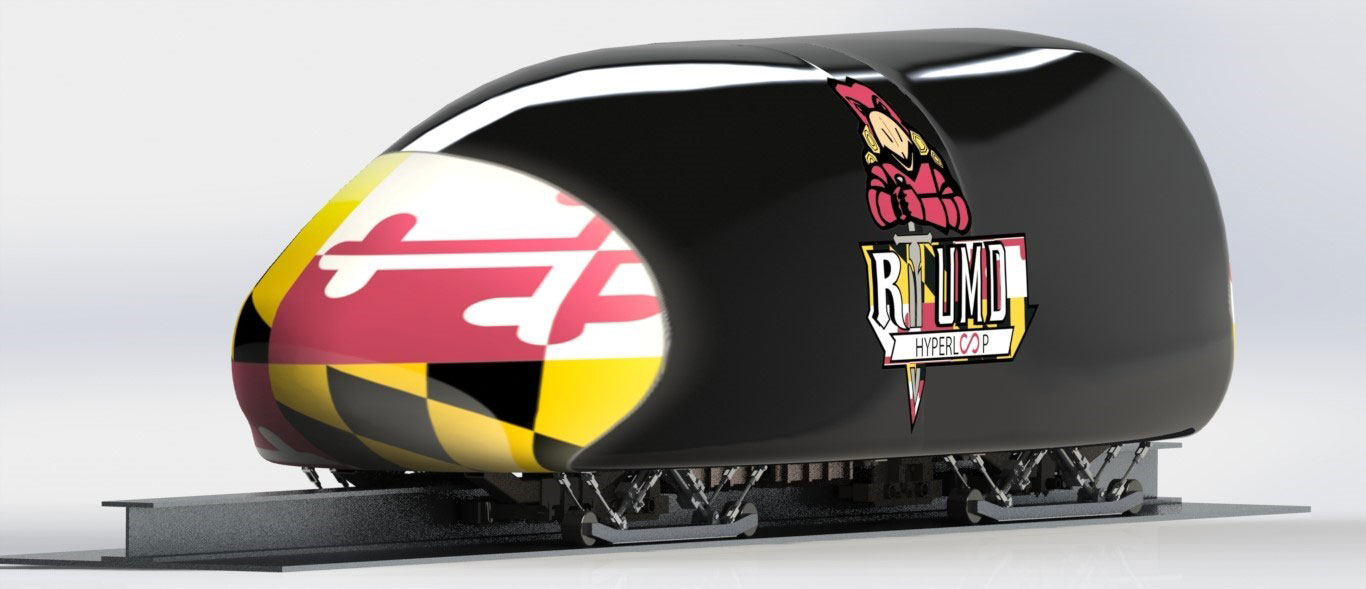

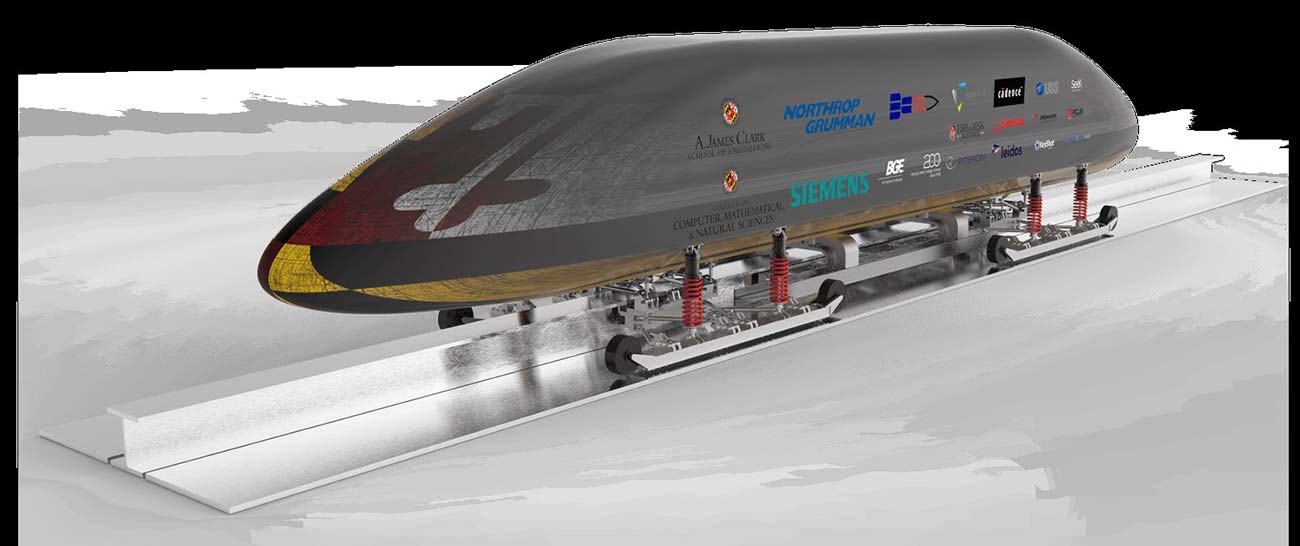

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: We're competing in the SpaceX Hyperloop competition where they're building a test rack and we're building a pod.

Hyperloop is an evacuated tube with a levitating pod traveling through it. The idea's been around since the early 1900s. A pod is a capsule that contains people-a short version of a train with one car. Think of it like a bullet train traveling through a low-pressure tube. You're taking all the air out of the tube to make it easier for things to travel through it, and you have a levitating vehicle so there's no rolling friction and no air impeding the travel.

Charley Morton: What makes it levitate?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: There are a few ideas on how to make it levitate. Ours uses magnets—arrays of neodymium permanent magnets, the strongest natural permanent magnet on Earth. We have an array of permanent magnets that travel over a conductive surface, an aluminum sheet on the bottom of the track. As those permanent magnets get moving, the relative velocity between the magnets and the aluminum surface induces a current into the aluminum, which then, in turn, generates a magnetic field that opposes those magnetic arrays. This is a product of Lenz's Law or Faraday's Law of Induction.

Charley Morton: So, let me see if I'm getting this. You're inside a tube, the air has been taken out of the tube, and you use magnets to propel the pod forward?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Onboard the pod you have these permanent magnets that allow you to levitate at speed and they will also keep the pod centered. But the propulsion for the actual Hyperloop is electromagnetic, and it's in the track. That's why the Hyperloop is so energy efficient: you're taking the propulsive system and putting it into the track (not the vehicle).

Charley Morton: So it's not gas-powered?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: It's electrically powered, so you can power it with any energy source: solar, wind, nuclear or even coal if you needed to.

Charley Morton: How fast could it go?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Theoretically, the limit is how fast you can turn with a person in there and not have them die! So, the theoretical limit is something like 2,000 miles an hour—Mach 3! Right now, they're shooting for just under the speed of sound, at about 600 or 700 miles per hour.

Charley Morton: Whoa!

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Yes. Our pod will only travel about 250 miles per hour, but that's only because we're going for a mile and we need room to stop. We aim to complete the mile in under 20 seconds from stop-to-stop.

Charley Morton: Tell me about the competition.

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: The competition originally started in June 2015 and they had over 1,200 teams enter. We made it through two cuts: first, the preliminary design package; then, at the next round of competition there were 128 teams for Final Design Weekend at Texas A&M University, where the field was then cut to 20 teams. Then they added 10 more to make 30 teams for the final competition.

We have about 30 people on our team.

Charley Morton: What kinds of backgrounds do team members have?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Most of the people on the team are aerospace engineers and physics majors. We also have mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, a graphic design person and a journalism major. Some people are getting double degrees, like in math and computer science.

Charley Morton: How did you get involved?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I had never heard of the Hyperloop, but a lot of people who have been following [SpaceX founder] Elon Musk heard about it. A friend told me about the competition. I joined the team and got hooked on the idea because I realized the implications it would have for society if we are able to develop this technology.

Charley Morton: Like...

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: The biggest advantage of a Hyperloop is that it's not just faster and more energy efficient, it's also cheaper to build because it requires simpler infrastructure. The initial costs they speculate are about one-tenth of a highway or a bullet train per mile. That reduced cost allows them to be built much more easily. Once it's built, you can connect existing population centers so much more quickly. You could get someone from Washington, DC, to New York City in about 15 minutes.

Charley Morton: Wow. When I checked it out, I found that, currently, the fastest train from DC to NYC, the Acela, takes about three-and-a-half-hours. And flying one way takes around one hour.

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: The Hyperloop can also carry goods. The way I see this, I could see building out something like "specialty" cities and connecting them with the Hyperloop. So, City A might specialize in being a great place to live, with X number of farms nearby, and X number of grocery stores, and everyone has their own land. Then connect that with a Hyperloop to City B, which is designed around a business center, with lots of restaurants and skyscrapers.

Then connect both those cities to an industrial center so people can commute easily from this nice City A and you don't have to have population centers that also support an industrial base and a supporting business center in City B. You can spread those things out for a more efficient use of land, with fast and easy commuter access between each of these.

Charley Morton: Would you maybe need city planners to design each of these areas?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Absolutely. Look at during the Industrial Revolution, the impact that the railroads had on that and the way that changed cities. Now make that train go five to ten times faster and it'll have a huge impact. It allows you to look at cities differently.

Charley Morton: Wouldn't that segregate people more than they already are?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I think it brings them closer together. Right now, where I live in Montgomery County, Maryland, you pay a hefty price for being close to Washington, DC, because there are more opportunities to work. But now you could quickly connect cities that are far away where people wouldn't necessarily have that opportunity, and give them quick access. So, someone living in the middle of West Virginia can go to school, or work, in DC, yet doesn't have to pay that "entrance fee" of living in a very expensive area.

Charley Morton: What about the cost of taking the Hyperloop every day?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: The lower cost to build it versus, say, a maglev bullet train, means that you don't have to charge a lot for tickets. Of course, that depends on where the funding to build the Hyperloop is coming from. I see it as a private-public joint venture. If the government were to fund it, they could charge relatively low rates—maybe five to ten bucks to travel from Washington to New York. I'd guess you could charge a rate that was cheaper than the cost of gas and parking.

Charley Morton: What kind of courses of study would someone have to take to get involved in a project like this?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I'm going to say physics because, as a physics major, I'm a bit biased. I truly believe it gives you a physical intuition for things like this. I'm also coming to realize, too, that anything you do in life, you're going to learn best on-the-job. Your coursework is important because it helps you develop a foundation. The engineering courses prepare you for how to engineer something properly, too.

But I think the biggest thing is really learning how to learn. Not just to show up and work on something, but to show up and figure out what you need to learn before you even do anything else.

We design our pod using CAD (computer-aided design) software. Lots of people on our project coming from a physics background have never used that. We had to learn it on the fly. The biggest thing was embracing the challenge of how to tackle a job that you can't really be prepared for in advance.

Charley Morton: Yikes! That sounds like a ginormous challenge—not knowing how it will work or what the pod even could look like. What's that like when you're working with a big team where your team members come up with all kinds of different perspectives?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Every single person's perspective is incredibly valuable. There's a lot of difficulty, but it pays off in establishing a culture where everyone's opinion matters and working to make sure that everyone is communicating effectively, because a lot of stuff can get lost in translation.

Charley Morton: Don't I know it!

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I think the effort spent going into developing a good communication network is incredibly important.

Charley Morton: Do you have to have a common vocabulary?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Not necessarily. We have team members from other countries who came here with different languages and cultures. It's not just that this person is an engineer and that person is a computer scientist—the same word may mean something different in what they do. The biggest thing in a team like ours is to be able to express when you don't understand someone, and to be willing not to assume what something means to one person is the same thing it means to another.

Ask questions!

Charley Morton: So, curiosity...

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Curiosity is incredibly important. Flexibility is important—not to be pigeon-holed with one solution. As a leader of the project, I have to look 10 to 15 steps ahead. That means not assuming that there's one right answer given where we are at a certain point in the project, but looking at the big picture.

Charley Morton: What about creativity?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: People think mathematicians and scientists and engineers are not creative, that they're all practical, logical people. But a huge component in solving a problem is the creativity in it—the ability to look at things a million different ways. The way I think of it, it's the ability to look at one thing in many ways, and then it can be your interpretation of it... that's one of the most important things to this project, because nobody's ever built one of these Hyperloop pods before. You have to be able to make something out of nothing.

Charley Morton: What's the biggest challenge you've found so far?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: Not fully fleshing out a design before we start building! We tried to rush something out to get built, and it ended up costing us a lot of time. We wanted to decide immediately. And being decisive is important, but the wisdom to recognize when you shouldn't rush into a decision is a challenge we've had to learn.

Part of the learning process is learning to be humble and question everything before you settle on one correct path to go down.

Charley Morton: Do you have any good stories to share?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: When we were getting ready for our final design proposal, we were going through different ways of levitating our pod. At the time, we were using these hover engines. And deep down inside, I knew that it wasn't going to be a good way of doing it: they required a huge battery on board and they were incredibly expensive and not energy efficient, so it was going to cost us a lot of energy to both levitate and control. We didn't really have any other solution, so we just got wrapped up in pursuing this way of operating the pod.

We were giving a presentation to our professors to get their feedback. At the end, I told my team members I wasn't confident about proceeding this way. I knew it wasn't right. After our team meeting, a few of us stayed behind to fix this. We geared up for staying awake for 72 hours until we figured it out.

We thought we could use permanent magnets to do it, but we had no mathematical basis to prove it. We wanted to pursue it mathematically, to prove that it would work.

It was a long three days. My friend who was doing the bulk of the math said it would take him a few weeks to come to a decision one way or the other; he needed to do these complicated formulas that were not fun.

So, another buddy and I went to get some snacks to gear up. But by the time we got back from the store, [our resident mathematician] told us he'd made an approximation that allowed him to say yes, this would work. It reduced the cost of our pod by $150,000 overnight. We no longer needed a huge battery on board. We had an epiphany where we had a new way of doing things!

The lesson we learned is to constantly question what everyone else is accepting as the truth because, a lot of times, there will be a better way of doing things.

Most team members wanted to go along with group-think: this is what we need to pursue. It seemed like they were scared to think outside of the box.

Charley Morton: What's your dream coming out of this experience?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I would like to see Hyperloops being built and help design cities around Hyperloops. The overarching dream is to help develop and implement technologies in ways that will directly benefit society.

My definition of that is increasing freedom and opportunity to everyone around the world. The Hyperloop is one tool to do that.

Charley Morton: Do you think with the Hyperloop challenge, you're inventing the future?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: My definition of that is increasing freedom and opportunity to everyone around the world. The Hyperloop is one tool to do that.

It's a magical experience to do something with a team of people who are as passionate about it as you are.

Charley Morton: Any advice to young people about pursuing their passions?

Erich Robinson-Tillenburg: I want more people to do that! Let's not just accept the idea that this is the world we live in, but let's find a way to make the world better—and here are some steps we can take to do that:

- Read a bunch of books to get a ton of different perspectives on things. That can be true for anything you want to do in life.

- Don't assume everything is going to be perfect. Acknowledge the risk, but don't be afraid of taking that risk.

Following your dreams is not going to be an easy thing, but be willing to work however many hours it takes to make those dreams happen.