Smoking gun: Asian gerbils, not European rats, caused the plague.

No doubt if such news had appeared in the broadsheets of, say, 14th century Italy (and did the have anything even remotely resembling a newspaper for informing citizens in those largely illiterate days?), trade with Asia would have been banned, and the traders themselves shipped back to their home port.

Today, it’s forensic archeology informing history–and our understanding of the progress of civilization. Medical detectives sniffing into the corners of history and civilization to determine how diseases start, why they spread, and how tree rings offer the smoking gun tracking shifts in climate.

You may have guessed by now that the true purpose of this blog, under the guise of Leonardo’s fabulous and inventive mind (so emulated by our heroine of Edge of Yesterday, Charley Morton) is to explore what’s on my own mind. What’s got me thinking right now? Would I might have known–way back in the ancient history of my formative years–that biology + archeology + anthropology + history = a way to figure out how disease spreads through history and affects the story of the world, how different my own history might be!

What triggers this revisionist thinking of career potential from my younger self? I recently ran across a story of archeologists digging up a mass grave containing human remains more than 1,500 years old under the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy–the beautiful museum where some of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpieces are on permanent display–these skeletons now thought to be victims of an early plague.

Amid growing national concern about the trickle of qualified candidates to fill a growing number of jobs in technical fields requiring strong skills in science, math and engineering, the question is increasingly important: how to entice young people into pursuing STEM careers that may not crop up in the normal course of Middle School Career Day? We live in times where how we define work, and what occupations are available, are in vast flux. The doctor-lawyer-teacher professional triad is still viable, but the world is changing. Doctors are not the only health workers. Law is narrowing for newly-minted JDs. Teachers are not revered, much less adequately compensated.

The careers of the future open up vastly different opportunities for young people today–and exposure to those possibilities can open vistas and ignite curiosity and the imagination.

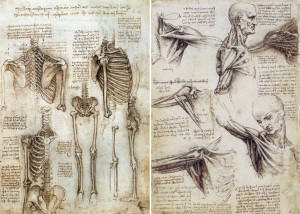

As usual, Leonardo da Vinci’s example, a passion for learning and seeing in new ways–leads us to new insight. He let his nose–and eyes and chalk–lead in his passion to understand the world around him. His fascination with human anatomy led him to grave robbing and even using the underground morgues in the Vatican itself to gain access to skeletons that would allow him to study human skeletal structures and the undergirding of the face that allowed him to draw and paint such lifelike, living humans in those masterpieces that come down to us today. In fact, had Leo known of the destruction beneath a gallery that displayed his masterpieces, he might have even been tempted to exhume the bodies himself, in his constant search to portray the human form in all its guises.

There was also the fascination with life, death, age, youth and nature–so present in Leonardo’s age and, paradoxically, so remote and isolated in our own. The contrast between beauty and death is one that captured Leonardo’s attention throughout his prolific career and revealed itself in his painting, sketching and sculpture.

Of course, in 1492 and beyond, Europeans were not the only victims of disease-carrying ships. Historians have documented the link between Europeans arriving in the New World and the subsequent spreading of disease among Native American populations, peoples who had no immunity to diseases carried by their conquerors, and the germs they carried with them. But until fairly recently, understanding how conquest went viral–and often deadly–was not a meme of history.

Could modern medicine, with its vaccines, antibiotics and advanced treatments for infectious disease–if known back in the days when barbers were surgeons–have eradicated the Black Death and changed history? Do we even know what the picture might have looked like if millions of lives that were erased due to plague, cholera, and other epidemics, had been controlled by better sanitation, isolation against the spread of disease and contemporary public health practices had been available back in the day?

Not to say we don’t have uncontrollable scourges today taking lives, Ebola being only the latest example. But today a new form of virus, proving just as infectious, is carried through ether of the World Wide Web and delivered electronically into our homes. As yet, the consequences of computer viruses are still being tested–ranging from terrorists recruiting members with their chilling videos extolling killing in the name of God, to warnings about spying from supposedly preventive and benevolent sources such as the US National Security Agency. Will the spread of such viruses will impact our future story for good or ill? History–and future digital forensic anthropologists–may someday uncover evidence that these have alternatively helped or hurt our world.

Had such an example of sleuthing research and discovery been available to me in my own formative years, I might have honed my love of writing, my aptitude for explaining science through story to then dive into biology, anatomy, environmental science, medical history and tracking the global trail of infectious disease to pursue a much different, but highly satisfying career path.

Growing up, my daughter had a pet gerbil. Scribbles seemed innocent enough–and certainly no great threat to the health of our family, except when it came to cleaning his cage, a task which would have been neglected completely were it not for the smell, and a good bit of nagging on the part of the parents. [So much for children promising to take responsibility!] A gerbil in the wild, stealing on a sailing ship for a three week journey in less-than-optimal conditions is undoubtedly a different beast than his domestic ancestors in the neighborhood pet store.

Who knew? And what young person today, cleaning her gerbil’s cage and wondering about her pet’s family history, might awaken a new interest in how such things work that takes her out of the classroom, into the lab, and onto the road of discovery in other yet-to-be-imagined ways?

Smoking guns may define the history of our past. But, for now, my bet is on the gerbil to sniff out the future history of health.

Et tu, Scribbles?